|

|

|

|

A CLOSER LOOK:

Distinguishing Similar Roman Republican Coins

Part II - Anonymous Victoriati

Kenneth L. Friedman and Richard Schaefer

|

|

|

|

In the first of this series of articles (published in the September 2009 issue of

“The Celator”), we noted that Michael H. Crawford’s indispensable Roman Republican

Coinage, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1974 (“RRC”) leaves some

classification uncertainties. This article is a guide to classifying the anonymous

victoriati.

|

|

The Introduction of the Victoriatus

|

|

Up until about 211 BC, Rome’s silver coins were similar in weight and

silver content to the staters (didrachmas) of Magna Grecia (southern Italy and Sicily).Until

the Second Punic War (218 BC - 200 BC), the production of these silver coins was

rather modest, reflecting a use in trade with the cities to the south rather than

a full internal monetization of Rome. The exigencies of the war with Carthage created

a much greater need which was met by the extensive minting of didrachmas known as

quadrigati (the reverse showed Jupiter driving a four horse chariot, a quadriga).

After the terrible defeats at Cannae and Trebia, Rome was forced to lower the quadrigati’s

weight and fineness.Some of the last quadrigati weigh less than five grams and are

less than 50% silver. With Rome’s success in the siege of Syracuse, the wealthiest

of the Sicilian cities then under Hannibal’s control, Fortuna’s wheel rotated quickly

and dramatically to Rome’s favor, creating a large influx of wealth, much in the

form of silver brought back from Syracuse. Rome, with its masses of citizens and

socii (allies) under arms, was swiftly becoming a fully monetized economy and the

sudden availability of enormous quantities of silver led to the creation of a new

monetary unit, the denarius, a coin of, perhaps, one and a third times the weight

and silver content of a traditional drachma of Magna Grecia.1

First issued c.211 BC, the denarius was struck on the weight standard of four scruples

(1 scruple equals about 1.12 grams). However, Rome recognized the continuing need

for coins on the old didrachma/drachma standard (probably for the purchase of supplies

from, or other trade with, or outright bribery of, the cities and aristocracy of

Magna Grecia and/or payment of allies from the cities serving with the Roman army).Therefore,

at roughly the same time, Rome created a second new coin called a victoriatus, struck

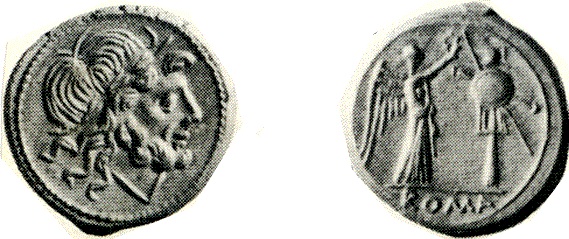

on a three scruple standard. Victoriati bear the head of Jupiter on the obverse

and Victory erecting a trophy on the reverse with ROMA in the exergue.2

While the denarius and its fractions were good silver (often reaching 98% fineness),

the victoriatus was a debased coinage throughout its production c.211-170 BC. It

averaged about 70% silver (but with considerable variation) and, unlike the denarius,

bore no indication of value. Thus intrinsically a victoriatus was worth roughly

half a denarius (75% x 70% = about 50%). But if one didn't know it was

debased and so judged simply by weight, one would have thought it worth 3/4 a denarius

(3 scruples compared to 4 scruples). In hoards, victoriati are almost

never found mixed with denarii, but rather by themselves. This indicates its

debased nature was well known in the Roman world. On the other hand, victoriati

were made for forty years, so Rome must have felt they had some success.

All of the victoriati (and the double and half victoriati) are technically anonymous

as none bear the name of any moneyer. However many of the later issues bear monograms

or symbols that tie them to corresponding companion issues of denarii. We

treat here 14 fully anonymous issues, meaning issues not only with no moneyer’s

name but also without any symbol or monogram. These are Cr. 44/1, 53/1, 67/1,

70/1, 71/1c, 83/1b, 89/1b, 90/2, 91/1b, 92/1b, 93/1c, 95/1c, 96/1 and 166/1.

Those that have been paired by Crawford to issues with symbol or monogram (being

similar except for the omission of the symbol or monogram) are noted in the list

below. For example, 91/1a is the victoriatus with symbol torque, so 91/1b

is denoted as “91/1b (No Torque)”. Crawford describes the obverse of each

of these 14 coins as “Laureate head of Jupiter r. border of dots.” and the reverse

of each as “Victory r., crowning trophy; in exergue, ROMA. Line border.” 3

|

The Diagnostics

In dividing the anonymous victoriati into 14 separate issues, Crawford has followed

the work of D’Ailly and Mattingly. In examining the victoriati the critical features

that distinguish the types are primarily (a) Jupiter’s hair and (b) the features

of the trophy. Weight is of almost no help because all but Cr. 166/1 are based on

3.2 grams standard. Cr. 166/1 is substantially lighter at approximately 2.7 grams.

As will be seen in the illustrated coins, Jupiter’s hair can be (i) “perpendicular”

(generally perpendicular to the wreath, (ii) “biperpendicular” (with both an upper

ascending half and a lower descending half generally perpendicular to the wreath),

(iii) “confused” (neither parallel nor perpendicular). The trophies vary widely.

Some have and some omit greaves. Some feature a skirt behind and below the shield.

Some of the trophies have a base (sometimes no more than a horizontal line immediately

above the exergual line, sometimes a more elaborate part of the trophy). All of

the trophies have a spear and a sword (or part of one) attached behind the shield.

We call the long line that projects from the top left above the shield, passing

diagonally behind it and projecting to the bottom right a spear. A second, shorter

line starts on the left below the spear, passes behind the shield, and then appears

on the right. This second line usually, but not always, features a hilt to the left

and a scabbard to the right of the shield so we call it a sword. Normally the spear

and shield cross, so the sword scabbard is above the spear on the right however,

on a few issues, the spear and sword are parallel. The hilt and scabbard are sometimes

missing or so cursory as to defy identification. On Cr. 83/1b, for example, they

have become merely large dots. In describing items to the left or the right of the

trophy, we use the convention of the viewer’s left or right.

|

RRC 44/1

|

All the known Groups are:

44/1 Group A. - Greaves on trophy but no skirt or base.

|

|

Fig. 1

|

44/1 Group B. - Skirt on trophy but no greaves nor base .

|

|

Fig. 2

|

44/1 Group C. - Base and skirt on trophy but no greaves (Fig. 3 and 4); sometimes short line below skirt (Fig. 5).

|

Fig. 3

Base and skirt on trophy but no greaves.

Sometimes the base may be an inverted V-shape as shown here,

and Group D (Fig.6)).

Fig. 4

Second example with base and skirt on trophy but no greaves.

Fig. 5

Sometimes short line below skirt.

|

44/1 Group D. - Base and greaves on trophy, but no skirt .

|

Fig. 6

|

44/1 Group E. - Trophy with neither base nor skirt nor greaves.

|

Fig. 7

Trophy with neither base nor skirt nor greaves.

|

|

RRC 53/1

|

53/1 - Perpendicular hair, greaves and small base on

trophy.

|

|

Fig. 8

|

53/1 - Skirt of two vertical lines

each with short horizontal line at bottom.

|

|

Fig. 9

|

53/1 - Tall and wide head, simple skirt

|

|

Fig. 9

|

53/1 - Skirt with interior pleats

|

|

Fig. 11

|

53/1 - skirt with pleats, Long, two

dimensional wing feathers

|

|

Fig. 12

|

|

RRC 67/1

|

67/1 -Skirt, Greaves, and Base on Trophy.

|

|

Fig. 13

|

|

RRC 70/1

|

70/1 - double skirt

|

|

Fig. 14

|

70/1 - Double Skirt variation

|

|

Fig. 15

|

70/1 - Thick post

|

|

Fig. 16

|

70/1 - Narrow post, no double skirt, Short

bar under skirt

|

|

Fig. 17

|

70/1 - Narrow post, no double skirt, no

short bar under skirt

|

|

Fig. 18

|

70/1 - wreath with single row of

leaves obverse variant

|

|

Fig. 19

|

|

RRC 71/1c

|

71/1c -small trophy base.

|

|

Fig. 20

|

71/1c - Small trophy base variation

|

|

Fig. 21

|

|

RRC 83/1b

|

83/1b - No Spear , Bulbous trophy base

|

|

Fig. 22

|

|

RRC 89/1b

|

89/1b - No Club, trophy base with two separated short strokes

|

|

Fig. 23

|

|

RRC 90/2

|

90/2 - elongated, narrow head

|

|

Fig. 24

|

|

RRC 91/1b

|

91/1b - Greaves as narrow ovals, neck curls projecting back at 45o

|

|

Fig. 25

|

|

RRC 92/1b

|

92/1b - No CROT

|

|

Fig. 26

|

|

RRC 93/1c

|

93/1c - No MP

|

|

Fig. 27

|

|

RRC 95/1c

|

95/1c - No VB

|

|

Fig. 28

|

95/1c - No VB variation with skirt but no greaves nor base

|

|

Fig. 29

|

|

RRC 96/1

|

96/1 - Incuse Roma

|

|

Fig. 30

|

|

Note that we have not classified the three anonymous Cr. 98/1 variants illustrated in RRC.

They are simply sui generis, until more examples are available.

|

RRC 166/1

|

166/1 - Wreath Below Spearhead, jupiter with wild strands of hair

|

|

Fig. 31

|

166-1 - Variation with neat hair

|

|

Fig. 32

|

|

A reader with a computer and internet connection at hand will find it helpful to see some on-line examples.

Several can be found at:

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database.aspx

In addition, Crawford illustrates all these issues in his plates.

Our thanks go to(in alphabetical order) Phil Davis, Pierluigi Debernardi and Rick Witschonke for improvements to this article.

Any remaining errors are ours.

|

Footnotes

1 This is, of course, a simplification as the staters of the cities of southern Italy and Sicily were not of a uniform weight standard and varied

over time. As Rutter notes at page 8 of his Historia Numorum Italy (London, 2001), during the 3rd Century BC the most common weight standard of a

nomos (i.e., a stater or didrachma) had been reduced from 7.8 to 6.6 grams (and thus a drachma of 3.3 grams). He continues, at page 9 by stating,

“Some time before the outbreak of the Second Punic War in 218 all silver and gold coinage had ceased in the Greek cities, though in the area south

of Campania there is little evidence from finds that the growing output of Roman silver had penetrated to any significant degree. With the arrival

of Hannibal in South Italy, however, some communities threw off their allegiance to Rome and coined in all metals to finance their bid for independence.”

This makes the comparison of the denarius and the victoriatus to Magna Grecian staters a bit tenuous but not without some meaning.

2 The reverse device is generally accepted as being derived from, and is certainly very similar to, the reverse of Tetradrachma of Agathokles of

Syracuse struck between 310 and 304 BC at about the time of Agathokles’ siege of Carthage in 310 BC (See Sear, Greek Coins and Their Values coin

974 or SNG ANS 680). This is a rather nice illustration of the use of coinage as propaganda, asserting to the people of Magna Grecia that the Romans,

too, were going to invade and defeat Carthage.

3 The one exception is Cr. 96/1 which describes the ROMA in the exergue as “incuse on tablet.” This is the only distinction Crawford makes in any of these coins.

|

Quick Finder Guide (follow from top to bottom)

|

1. ROMA incuse Cr.96/1 |

|

2. Rev. bulbous trophy base and helmet without crest Cr. 83/1b |

|

3. Skirt with greaves Cr. 67/1 |

|

4. Unconnected base and skirt of ~5 short vertical strokes Cr. 89/1b |

|

5. One or both greaves are ovals; 3 or 4 bottom curls project backward Cr. 91/1b |

|

6. Stern long head with perpendicular hair and very long curls Cr. 90/2 |

|

7. Placid long head with biperpendicular hair

Cr. 95/1c |

|

8. Light weight, small flan, sloppy engraving; wreath below spear; usually some

wild hair strands Cr. 166/1 |

|

9. Squashed Victory and trophy; small head of Jupiter with three long,

close straggly curls Cr. 93/1c |

|

10. Aggressive large head in fine style, skirt and base Cr. 70/1 |

|

11. Reverse simply engraved with open space; trophy has skirt, but no greaves nor base; 3 diverging curls Cr. 92/1b |

|

12. Fine head, perpendicular hair, small base, no spear left of shield Cr. 71/1c |

|

13. Excellent detail on both sides, elegant (usually) squarish head, no base Cr. 53/1 |

|

14. Having eliminated all the above issues, is the head tall with stern look and confused beard? Are the wing feathers isolated lines? If so Cr. 44/1 |

|

|